The Unknown Story Of This Famous Rembrandt Painting Is Finally Uncovered After Centuries

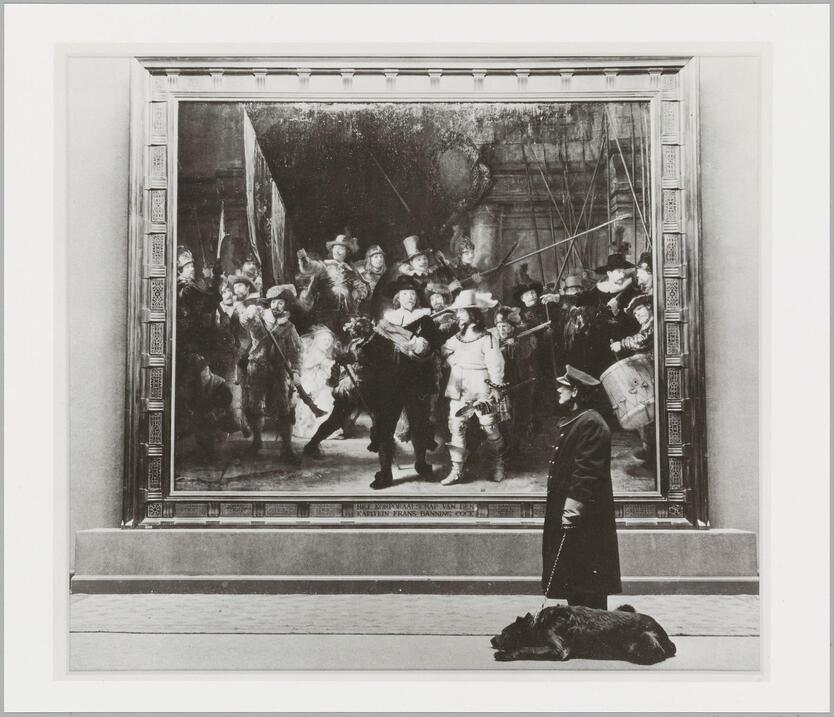

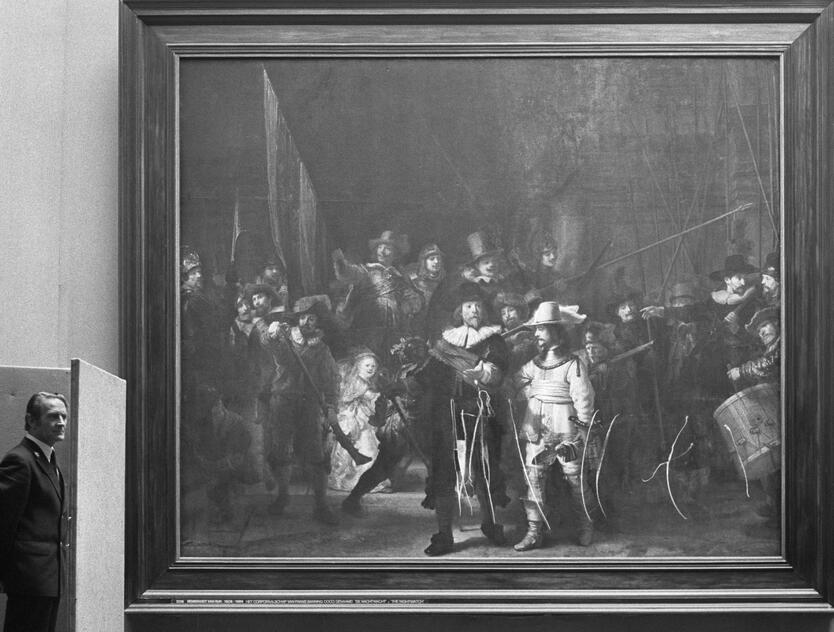

The Night Watch, one of the most famous paintings by renowned artist Rembrandt van Rijn, is awe-inspiring because of its beauty and massive size, with a total of 4.6 meters in length and 3.8 meters in height.

A project has been launched to gain a better understanding of the master painter’s technique to analyze this piece right down to the chemicals in it.

The Night Watch

The painting shows 31 figures in all, with Captain Frans Banninck Cocq front and center. What makes this painting memorable is the fact that the scene looks chaotic, unlike other paintings from that era where subjects would normally be lined up in full portrait style.

Source: Frans de Wit/ Wikimedia Commons

Rembrandt stepped away from the norm by showing them in action, with the guardsmen brandishing their weapons. There are other more minute details, too, like the little girl lost in the crowd and a dog barking at the drummer.

Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum

The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam has been the proud home of The Night Watch for over 200 years. It deserves its place in the Gallery of Honour, where it remains the focal piece amid other Dutch paintings.

Source: Voytikof/ Wikimedia Commons

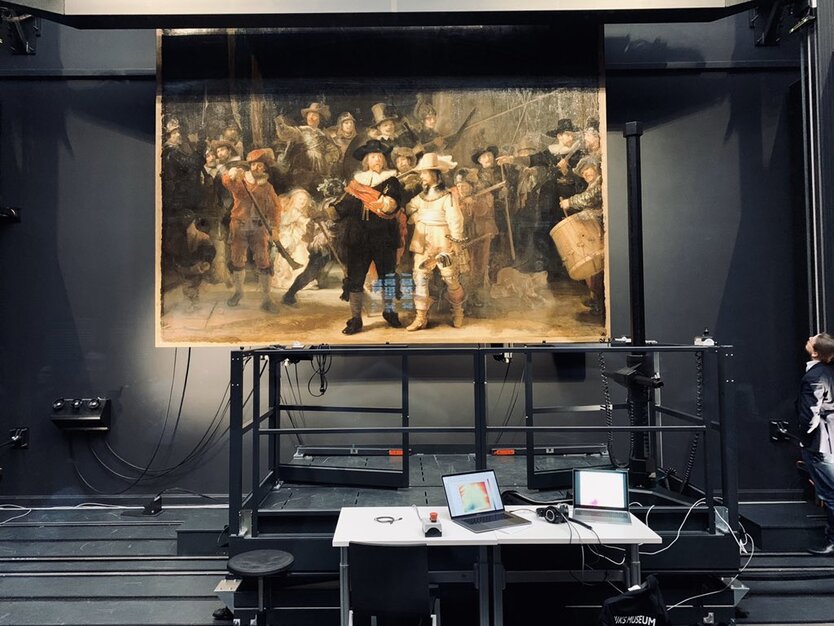

One Wednesday in August 2019, visitors were surprised to see The Night Watch out of its frame. A pair of scissor lifts stood in front, hiding half of the painting from view. On the lift sat a macro XRF scanner, which is used to study chemical elements.

Operation Night Watch

Possibly, one of the most fascinating things to learn about a centuries-old painting like The Night Watch is how it has changed over the years. That’s why the Rijksmuseum launched Operation Night Watch, a research and conservation project where experts can analyze the painting at a molecular level.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The team of historians, chemists, conservators, and computer scientists can get more details on Rembrandt’s creative approach to this masterpiece. This study will also show how the painting has changed over the years.

Fusing Science and Art

One thing that makes Operation Night Watch fascinating is how it mixes science and art. The data gathered from this project can change how people see artworks over time. It can also impact the methods used in restoring historical pieces like this.

Source: Vincent Fournier

On the day they started Operation Night Watch, conservators Anna Krekeler and Susan Smelt stood on top of the lift and got ready to start the project 30 minutes before the museum opened its doors. They positioned the scanner around one centimeter away from the painting’s surface.

Scanning Commenced

Susan shares that there is so much detail on a painting’s surface, so it can never be seen as a flat area. That’s why they need to be extra careful with the positioning of the scanner.

Source: Hay Kranen/ Wikimedia Commons

Though they started at 8:30, it was around 9:45 AM when they finally completed the setup. The crowds had started trickling in at 9:00, so there was an audience who witnessed the scanner start its slow movement as it took in every detail of the painting from left to right.

In Full View

The Night Watch is one of the most popular pieces at the Rijksmuseum, bringing in an average of 2.2 million people each year. This is why they decided to perform Operation Night Watch during operating hours so visitors could watch the process.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The painting and the lift are encased in a glass box to keep visitors from coming too near while the scanning is ongoing. A yellow sign is also placed on the glass door, showing a notice that macro XRF scanning works differently than a regular X-ray.

Not a Regular X-Ray

Though a macro XRF machine also scans things, the data it delivers goes deeper than a regular X-ray. It doesn’t simply show areas where the X-ray is absorbed. A macro XRF scanner scatters the rays across the painting’s surface and then goes back to a detector. The machine then measures the energy from the returning rays, which then reveals what chemicals and pigments were detected.

Source: Encik Tekateki/ Wikimedia Commons

With this kind of technology, people can better understand the kind of work initially done on The Night Watch, as well as how conservation and restoration efforts have impacted the original work over the years.

A Complex Mix of Chemicals

Analyzing a centuries-old painting like The Night Watch reveals a complex mix of chemicals that gives people background on the artist’s techniques. For example, traces of lead would normally be associated with lead-tin-yellow or lead-white pigments.

Source: Peter Isotalo/ Wikimedia Commons

As for Rembrandt, he is known to use smalt. This much was evident in Operation Night Watch, which showed traces of cobalt, nickel, and arsenic in a type of blue glass. This, according to Susan, is a clear indication of the presence of smalt.

Black and White Maps

A total of 33 elements within the painting were studied, with the scanner producing black and white maps for each element. The elements in focus will shine bright to show which ones are predominant in each area.

Source: Vincent Fournier

For example, the areas with calcium will shine bright white on the calcium map even if this element is seen in dark parts of the painting. In this case, the boot of one of the figures (dark brown to the naked eye) appears bright white on the map.

More Than Meets the Eye

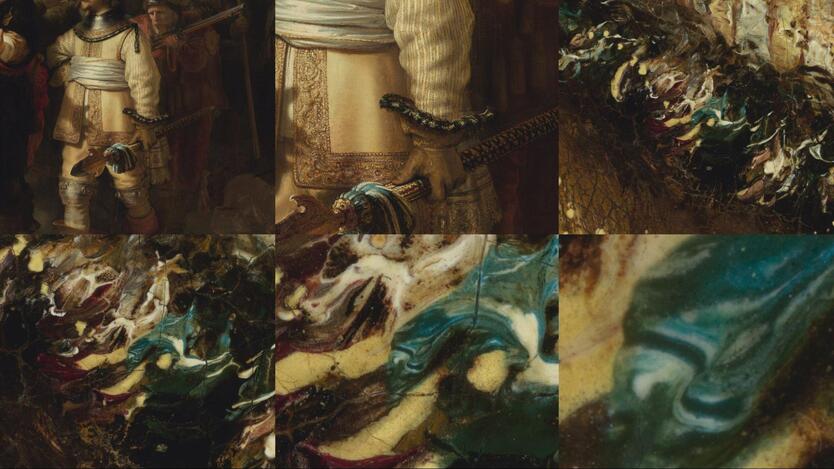

The analysis that Operation Night Watch is delivering proves one thing–that there is so much more to a painting than meets the eye. People will see different parts of the painting as simply white or blue, but the macro XRF shows that where one might think only brown paint was used, Rembrandt mixed a little blue into it.

Source: Rijksmuseum/ Facebook

Of course, no one can tell what Rembrandt’s purpose was for his approach. One can only assume that he might have used the blue smalt to make the brown pop out more. It’s also possible he used the element to make the paint dry faster.

An Artistic Genius

Rembrandt was indeed an artistic genius, considering the unique way he approached his paintings. Rijksmuseum’s head of science, Katrien Keune, also agrees with this, considering what they’re discovering with Operation Night Watch.

Source: Vasyatka1/ Wikimedia Commons

Katrien says she’s interested in discovering more about how the master created certain effects when he painted. For example, Rembrandt was well known for his technique called “impasto,” where he created a 3D effect by using thicker paint in some areas. Katrien agrees that this is what makes Rembrandt’s paintings special.

Revealing Secrets Below the Top Layer

The scans also reveal a lot of other things that lie beneath the painting’s top layer. This could give deeper insights into what was going on in the artist’s mind as he painted each part of the scene.

Source: Royal Talens/ Facebook

Did he change how the characters were positioned or add some elements as an afterthought? The researchers at the Rijksmuseum doubt that they’ll find anything that could change the course of history, but they do acknowledge that the deeper insight into the artist’s creative process is groundbreaking.

'The Night Watch' Through the Years

Another aspect that Operation Night Watch clarifies is how the painting has changed through the years. It has degraded over time and was subject to several restoration attempts that could have altered some elements. A whitish haze, for example, has appeared around the dog found in the bottom right corner.

Source: Rob Erdmann/ Twitter

The painting went through a major restoration in the ’70s, but nothing else has changed since then. This study could present a better look at how those restorations impacted the original work underneath.

Hours of Scanning

A total of 56 scans are scheduled for The Night Watch – each scan taking 21 hours to complete. This covers the entire canvas. Once the scanning process using the macro XRF is done, a high-resolution camera system set to take over 12,000 images will take its place. Other imaging techniques will also be done.

Source: Vincent Fournier

Once the data analysis is done, that’s the only time any conservation work will be completed. The data-gathering and imaging done will show which areas they should be restoring.

Serious Work Being Done

Though the scans were all done at the Rijksmuseum, the more serious work was being done across the road at a red brick structure called Ateliergebouw. This is where the researchers and conservators are based, analyzing all the data from the scans.

Source: Rijksmuseum/ Facebook

Oddly, this place does not look like an art museum at all. Instead, it’s like a lab straight out of a CSI set. Senior scientist Robert Erdmann has an office where he stares at paintings from his computer monitors.

An Unbelievable Amount of Data

Robert used to be a materials scientist in Arizona, but his interest in both science and art brought him to Amsterdam. He knew that the arts scene needed someone to help people understand each work of art through data. So, that’s what he did with The Night Watch.

Source: Rijksmuseum/ Twitter

Possibly the biggest challenge in working with The Night Watch is the insane amount of data that Robert has to work with. If they’re not careful, they could easily get overwhelmed with the data and get lost.

Smaller Than a Red Blood Cell

Robert estimates he deals with around 600 terabytes of data throughout Operation Night Watch. That’s because the Hasselblad camera pulls the resolution of The Night Watch to 4.75 micrometers, which means each pixel is smaller than a red blood cell!

Source: Rob Erdmann/ Twitter

Due to the sheer size of The Night Watch, this also means that when put together, the entire painting will be around one million pixels wide. This shows them paint pigments that are not even seen by the naked eye.

A Master at Work

All these tiny details make Robert appreciate the master at work, knowing that what he’s doing reveals every stroke and thought Rembrandt put into creating this masterpiece.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Robert recalls the work done on other paintings by Rembrandt, Portrait of Marten Soolmans and Portrait of Oopjen Coppit, where the same was done. He finds it fascinating to see each blob of paint and each stroke as he studies each data point, turning into a full image when he zooms out.

From Smudges to Images

If an outsider looks at Robert’s screen while he’s working, there will be moments when all you’ll see are smudges of different colors. You’ll see only these smudges when you zoom in on the high-resolution images.

Source: Vincent Fournier

For instance, if he zooms in on Oopjen’s pearl necklace, his screen will automatically be filled with gray and cream smudges. However, the moment he zooms out, you realize that you’ve been looking at pearls all along.

Putting Thousands of Puzzle Pieces Together

Another big challenge for Robert is putting thousands of scans and photos together to form a single image of The Night Watch. Not all of the images taken have the same lighting, for example. Some might have some distortion, while others could have been taken from a slightly different angle.

Source: Rob Erdmann/ Twitter

The trick here is putting all these puzzle pieces together so that the painting appears flawless. It’s like creating a collage but making it seem like a single image and not many separate pieces.

Spotting the Difference

Robert has laid out processes that make this already challenging task more doable. He created a technique called “curtain viewer,” where he can split his screen and have the cursor show the same point on multiple images.

Source: Rob Erdmann/ Twitter

This method removes the need to manually compare one image to another to spot minor differences. Robert uses a painting by Hieronymous Bosch as an example. One area in one of the images shows a difference in texture, meaning there used to be an element that was painted over.

Spotting the Overlaps

Robert uses the same technique on The Night Watch to show possible overlaps among the images he’s putting together. He compares element maps produced by the macro XRF scanner and figures out which pigments were used in specific areas. This paints a clearer picture of the entire piece.

Source: Wanderlust/ Facebook

Of course, the curtain viewer also has its limitations. That’s why he also developed a tool called “pixel swarm,” which covers more ground and can deal with all 33 element maps from The Night Watch simultaneously.

Studying the Elements

Robert demonstrates the pixel swarm by using the painting The Man in a Red Cap. He starts by creating a scatter plot that compares cobalt and arsenic and pinpoints areas where cobalt, arsenic, or both were present.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Then, he highlights these pixels and makes them blue. Although arsenic is known to degrade quickly, there’s a good reason why artists continued using it for their paintings–it leaves a golden finish. Because of this, Robert tags those specific pixels yellow.

More Discoveries

With the image of the painting now shining blue and yellow in different parts, it’s easier to see that the blue pigments are mostly found in the painting’s brown background. However, it’s also seen on the red hat’s edges. This means that the hat was originally smaller, and the edges were only painted later on as an afterthought.

Source: Vincent Fournier

There are also areas where some pixels show similar composition. It’s noticeable that the pixels close to each other are identical in chemical structure.

A Clear Timeline

Another interesting tidbit that Robert’s methods reveal is the timeline that the artist followed to complete the masterpiece. Centuries ago, artists mixed their paints, and these paints dried up very quickly. Because of this, painters often work on parts where the same colors would be used in one go.

Source: Rob Erdmann/ Twitter

This means that everything the artist painted in a single day would also have similar chemical compositions. For example, The Man in a Red Cap showed that on the same day that Rembrandt extended the red hat, he also made changes to the figure’s pose.

Discovering Irregularities

Robert also has a way of finding irregularities in a painting. Another Rembrandt creation, The Jewish Bride, is a good example. He used a neural network to show how it should look using nothing more than the data from the macro XRF scans.

Source: Rembrandt - Mia Feigelson Gallery/ Facebook

Once the original painting and the neural network’s output are placed beside each other, they are mostly similar except for some black speckles on the bride’s face. It shows calcium, which would cause the neural network to assume that those areas should be bone black.

Signs of Restoration

Although the neural network assumed that the presence of calcium meant that those spots on the bride’s face were supposed to be black, it reveals a different meaning. Calcium is also used in gypsum, an element used when restoring art pieces.

Source: Vincent Fournier

This means that those spots were not part of the original painting but something added later on in one of the past restoration attempts done on the piece. This type of method helps Robert verify the authenticity, as well.

A History of Conservation

Applying these methods to The Night Watch would definitely reveal a lot of interesting information, knowing that it has a long history of conservation efforts. It was originally displayed at the big hall in the headquarters of the civic guard, where feasts and target practices were held. It was a commissioned piece and was originally called Militia Company of District II Under the Command of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq.

Source: Rijksmuseum/ Wikimedia Commons

This means that the painting had been damaged in many ways before being taken in for proper care and restoration.

Unbelievable Damage

Conservator Esther van Dujin has begun digging into old archives to find documentation that would help her create a timeline showing the conservation history of The Night Watch. Her research connects the data gathered from the scientific imaging that Robert and the other scientists do.

Source: Txllxt TxllxT/ Wikimedia Commons

It turns out that unbelievable damage to the painting was also caused by the move from the militia headquarters to the Amsterdam town hall. Because of the painting’s size, they cut off sections of it!

Finding the Missing Parts

It’s a good thing there were other smaller copies that Rembrandt’s contemporaries created during that time. An 86-centimeter version made by Gerrit Lundens, a Dutch artist, is on display in the Rijksmuseum beside the Rembrandt original.

Source: Vasyatka1/ Wikimedia Commons

The smaller version shows that two more figures on the left are not on the original anymore, meaning these figures must have been cut off. They also found areas that show some canvas missing, as well as parts where it shows repair work done in the past.

Changing Techniques Over Time

As Esther studies The Night Watch’s history, she also sees how conservation techniques have evolved. The painting went through some restoration treatments and had its canvas removed and reattached again and again.

Source: Vincent Fournier

Even the varnish used during different restoration efforts changes throughout its history. Esther says the traces of the old yellow varnish popular in the 17th to 19th century were still evident despite the layers of new varnish applied over the years.

Temporary Fixes

Possibly the biggest problem with applying varnish over and over is the fact that cracks eventually start to appear on the surface, making the painting appear cloudy over time. Paintings also become more sensitive with age, so many restorers hesitate to add more touches.

Source: Rob Erdmann/ Twitter

Max von Pettenkofer, a German chemist, came up with a regeneration method that softened varnish and removed the cracks back in 1870. However, it was a temporary fix that was redone every ten years.

More Work Done

The temporary fix that was initially being used stopped working over time, so the museum had to think of a new technique. But World War II suddenly broke out, so The Night Watch was immediately rolled up and evacuated.

Source: Rob Erdmann/ Twitter

It was 1945 when The Night Watch was returned to the Rijksmuseum. Restoration began immediately. Layers of the old varnish were removed, and a new lining was added. As the painting was restored, experts realized that the painting’s gloomy nature was caused by the old layers of darkening varnish.

A Brutal Attack

When the ’70s rolled around, there were plans to restore the painting again. But it was brutally attacked in 1975, with a visitor slashing the painting vertically with a bread knife 12 times. This left some of the canvas dangling.

Source: Vandalized Night Watch/ Wikimedia Commons

Although the painting has been repaired since then, some scars are still visible if you look closely. Of course, the scans show this even more clearly, especially on the macro XRF element maps where some chemistry contrasts are evident.

Filling in the Gaps

To fill in some of the gaps in the painting’s conservation timeline, some old pieces of canvas used to repair The Night Watch in the past were brought in for OCT imaging. There was an old piece, for example, that was used to cover a small hole but was removed in the 1975 restoration process.

Source: Balou46/ Wikimedia Commons

This piece helped add some information on the additional layers of varnish on the painting, showing an even clearer picture of the immense work done on it over the years.

Getting Clarity

The OCT scans revealed that the small patch of canvas was added to the painting in the 19th century, making it older than they initially thought. It also shows signs of the varnish added after World War II when it was initially brought back to the museum.

Source: Rob Erdmann/Twitter

With data like this, it will become easier for experts to restore parts of the painting that need to be fixed. They now have a better idea of what’s causing the changes and the chemistry.

Doing Only What’s Necessary

Although their intentions were good, it is now more evident that old conservation techniques meant covering flaws without thinking too much about how they could impact the original work of art. That’s why more modern art conservation techniques ensure that anything not original should be removed, and pieces should only be retouched when necessary.

Source: Adrien Oyono/ Twitter

In the case of The Night Watch, they decided to wait until all the data was complete before deciding how further work should be done, including reapplying varnish and relining the canvas.

Restoration Ongoing

Restoration on The Night Watch was supposed to happen in mid-2020, but the pandemic delayed the timeline. Two and a half years after Operation Night Watch was launched, the painting was finally removed from its wooden frame and transferred to an aluminum one in 2022.

Source: Rijksmuseum/ Twitter

The last restoration project was in 1975 when the painting was vandalized, but this time, they had more data to help them figure out which parts needed the most attention. The study also helped them create a better strategy for safer restoration practices.